The very first article I wrote for my newsletter was a book recommendation for David Allen’s book Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity. That was 2004. Recently I realized that I had misunderstood the utility of a key tool from his system — the weekly review.

This is particularly ironic to me, because the one time I saw David Allen in person (at a talk), I told him I loved his system but had trouble implementing the weekly review. He paused, made eye contact, and said, “You have to do it.”

I was a little taken aback, but I thought I understood his point. It makes logical sense — if you don’t review your commitments on a weekly basis, you cannot keep them. I went back to the drawing board to figure out how to make a weekly review happen.

A weekly review evolves into a weekly planning session

The way David Allen explained it, a weekly review consists of reviewing every one of your projects to see what was accomplished in the previous week, so that you can determine what next actions to take in the coming week(s). He has a detailed process for doing this in his book.

The problem I had with this process is that I couldn’t complete it. More than once I invested 8 hours trying to review all of my projects without finishing. There were just too many of them, and they all needed some serious thinking. I came out of these sessions with enormous “next actions” lists that were impossible to deal with.

But I saw the logic of his point, and after my “talking to,” I resolved to figure out a solution. I needed some way to make this process doable.

I explained how I went about it in another article. Briefly, I gave myself a time budget of about 30 minutes, and did the best possible job I could do in that time.

I recommend this approach whenever you are overwhelmed by the complexity of a task. Get a quick and dirty overview in a short amount of time. Any complete overview, no matter how superficial, will help you activate the wider context. This is needed psychologically so that any decisions you make are made in context.

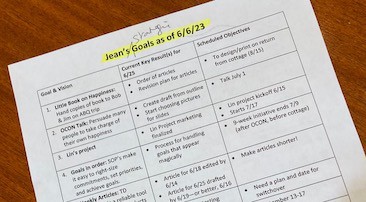

With hindsight, I see that my “weekly review” morphed into a quick weekly planning session. I didn’t try to go over the list of all of my projects — it was still too long to deal with in any reasonable way. But I did make a list of all of the top projects I needed to think about that week, so I could get a quick overview and make a rough plan. My explicit goal in these weekly planning sessions was to make the coming week more productive by identifying the tip-top priorities for the week. I believed it was more important to get at least a bit of direction (which I could do in a relatively short time) than to thoroughly review everything.

Over time, I got more and more effective at using those 30 minutes. These days I’m able to plan the week in reasonable detail in just half an hour. My weekly planning process definitely helped me to become more productive. I recommend this simplified approach to anyone who lacks a weekly process for keeping on top of productive work. You can read more about weekly planning in my article on Evolving a Weekly Planning Process.

The deeper problem: overcommitment

Although my weekly planning process helped me be more productive, it did not address the real problem I had with David Allen’s weekly review. I was overcommitted. This is something I’ve grappled with for years. Over time, by hook or by crook, I have gradually reduced my commitments from an insanely ludicrous number to just an unrealistically large one. Clarifying my central purpose helped. Delegating routine work helped. Long-term planning helped. Making tough decisions helped. Lots of things helped.

But with all of this, I am still trying to do noticeably more each week than is possible given my current knowledge, skills, and motivation.

Shall I run through all of the ways that this is a problem? Among other things, I never have a week in which I get everything done that I had intended to get done. This means that all of my projects are constantly in conflict with one another. I am constantly faced with a choice of whether to renegotiate a commitment I made to someone else or let my top intellectual projects slide. I am constantly trying to figure out a way to use the 80:20 rule to reach a finishing point on one project so I can move on to another.

In other words, not only do I have insufficient time to follow through on all of my commitments, I use up a good chunk of this time in overhead to juggle between the projects.

Why not just reduce my commitments? This is easier said than done. I have tried all of the obvious things to reduce them. I have often been ruthless in saying “no” to new commitments. In some cases, I have decommitted from major endeavors. But after getting some things off my plate, I always think up compelling new projects that I seem able to make room for, if I just move the meat and vegetables a bit closer together. Before I know it, I’m overcommitted again.

I think this pattern is a predictable effect of being ambitious, creative, and committed to personal growth. As anyone who regularly uses “thinking on paper” can attest, it’s amazing what you can accomplish as a result of 30 minutes of concentrated thinking. And as many Launchers will attest, it’s amazing what dramatic results you can achieve in a couple of months of focused effort. When you appreciate what your effort can achieve, you see wonderful opportunities for creating new values everywhere you look.

So the problem is, “what you can do” is a moving target. So is “what you’d like to do.” I think the solution to overcommitment is a deep self-understanding of your knowledge, skills, and motivation — including your present ignorance, incompetencies, and unresolved conflicts.

Any specific instance of ignorance, incompetence, or conflict can be remedied in principle with appropriate effort. But ignorance, incompetence, and unresolved conflicts in one’s mind cannot be eliminated per se. As you learn more, you also get clearer on the next thing you don’t know and could learn. As you gain skill, you also create new opportunities for action of a kind that wasn’t possible before — and therefore you are not yet good at. And as you achieve your values, you change the world and make new values possible. Whenever you set your sights on one of these new values, it takes a while to reintegrate your value hierarchy around your new conscious priorities. Until that is complete, you will have unresolved conflicts.

This isn’t to say that overcommitment is inevitable. Some very ambitious, creative people seem to manage their commitments just fine, though I wonder if they do so by forcing themselves to give up some things. I’m looking for an entirely value-oriented way to get out of this loop.

Tackling overcommitment

I decided to tackle the problem head on after I wrote some of my recent articles on happiness, specifically the one explaining what you need to know about suffering to be happy. Thinking about my own advice, it struck me that overcommitment was the #1 source of suffering in my life and I should do something about it. So I started an initiative to get my “goals in order.”

Fortunately, at the same time I was writing those articles on happiness, I was giving a series of 12 classes on rational goal-setting (available in the Thinking Lab). During that course, I realized that you only set a goal when you want to change the status quo. Moreover, there is a huge distinction between goals that require strategy — because you don’t know exactly how to achieve them — versus goals that are accomplished incrementally and almost inevitably through one’s “standard operating procedures.” Both kinds of goals require monitoring and course-correction, but strategic goals take substantially more effort. (See my article on Goals, Values, and Productivity for a bit more on this issue.)

This new clarity about goals gave me a great idea for reducing overcommitment. I could rethink how I was pursuing some goals such that I could gain them incrementally through standard operating procedures, instead of with a great focused effort (which was in limited supply).

To get started, I made a short list of strategic goals that I could review each day. My recommendation, based on general principles (the crow), is to have 7 strategic goals max. My list was 10, so I finished off some projects to whittle it down to 7. It immediately grew back to 10.

In addition, I found almost immediately that I also needed to track goals that are being achieved through standard operating procedures. For example, these days Thinking Lab classes require strategic thinking only when I am starting a new series. Once I am clear on the concept, I can work out each class in the series as I go, with 3-5 hours of work. But I still need to monitor my progress so I can course-correct and incorporate new information when a class triggers a surprising insight, which they inevitably do. I didn’t need to look at them every day, but I did need to look at them periodically.

So my list grew. It now has a front and a back — strategic goals on the front, others on the back, about 25 total. And my weekly planning process changed. I realized I needed to block out time for all of those “standard operating procedures.”

At first, I found it helpful to review my goal sheet each day. But after the list started growing, I noticed I started feeling resistance to going through it. It seemed like week after week, I didn’t have time for a couple of my strategic goals. In my weekly planning session, something new would come up that needed to get done this week. I was not solving the problem of overcommitment, I was just documenting it. I started to get a bit demoralized.

Processing conflicts with a weekly review

Whenever you are tempted to avoid looking at something, that is when you need most desperately more awareness of whatever it is, not less.

I realized I needed a structured way to raise my awareness of the conflicts inherent in being overcommitted. I needed not just a list of goals, not just a weekly planning session, but a weekly review session in which I deal with the inevitable conflicts between my commitments.

I needed to bring these conflicts into awareness so that I could think them through, at least one level clearer.

Duh. I think this was a key purpose of David Allen’s weekly review, which I feel like I have reinvented. He recommended you keep a list of all of your projects (which he defined as any outcome that required multiple steps), and review them all each week.

You need to look at them all to address the conflicts. It’s not enough to just use them to plan the week. (Incidentally, planning the week is not part of David Allen’s system, but I find it valuable. Planning the week takes an additional 30 minutes.) You cannot resolve conflicts without experiencing the conflict and giving the contrary motivation a fair hearing. Awareness is essential to the process.

My new weekly review consists of taking 30 minutes to write a paragraph about each of my 10 strategic goals. What did I get done the previous week? If not as much as I hoped, why? What got in the way? Was it really more important? What would I do another time? This is a gentle way to shed light on the issues that need my attention.

I do not expect my weekly review to work miracles such that I stop being overcommitted in one week or even one month. What I expect is that I will gradually bring to light and resolve the conflicts that keep me overcommitted. And in the future, as I want to add goals to my list, I will have a systematic way to think about whether they really fit into my life. I have created a doable weekly process for gradually growing my knowledge, values, and skills to support my strategic goals.

You don’t make such changes through an in-depth thinking session. You do it through value-oriented action, one choice at a time, plus a weekly review to take stock and nudge yourself in a different direction this coming week.

* * *

P.S. to Thinking Labbers: I’ve been fooling around with the term “maintenance goals,” which I’m officially retiring with this article. All goals are designed to change the status quo. Many are achieved through “standard operating procedures.” The few goals that need the most attention are “strategic goals.” These goals require you to figure out a strategy to achieve them. Often, once you get started, you will discover that your strategy was mistaken and that you need to come up with a new strategy. Most of our rational goal-setting class concerned strategic goals.

0 Comments