When you are committed to living by reason, contrary emotions can create all sorts of conundrums.

For example, a Thinking Lab member recently reported some doubts about a decision he made to take a break and go for a walk. Based on our discussion, I would say that all of the evidence pointed toward his taking a walk as being the best use of his time. He was mentally frazzled, so he needed to clear his head somehow before he could continue on the project he was working on. He didn’t have the mental resources to do anything complicated. Plus he had a conscious goal to add more enjoyable exercise to his days. Walking seemed to address all of these issues. But he was worried about his decision. His concern went something like this:

Logically I knew that going for a walk would be good for me. But what motivated me was not that. What motivated me was that the walk would feel good. Isn’t there a problem with that? Isn’t that going by emotion?

This is a great example of being honest with oneself. It would be easy to let this subtle conflict slip by with a casual rationalization of “it doesn’t matter” or “I’m sure it’s the right thing to do.” But his concern is justified.

When you take an action, including an action that is “obviously” your best choice, your exact reason for taking the action matters a lot, psychologically. The words you use to justify the action will have both a short-term and a long-term effect on your motivation.

In fact, taking the “right” action for the wrong reason is self-destructive.

Your reason for your action

Your reason is the answer to the question “why?” Why are you taking the action you are taking? There are only three types of answers:

a) You want fill in the blank with some apparent value.

b) You don’t want fill in the blank with some apparent threat or disvalue.

c) Any other answer that does not fit one of the simple forms “I want” or “I don’t want.”

Let’s flesh out some alternative answers for this situation:

Apparent values you could be after:

- I want to feel better.

- I want some fresh air and sunshine and nature.

- I want to clear my head.

- I want to stretch and get the blood flowing again.

- I want to re-energize.

Apparent threats or disvalues you could be avoiding:

- I don’t want to feel this way.

- I don’t want to do my work.

- I don’t want to be paralyzed.

- I don’t want to be sitting anymore.

Other:

- I don’t know.

- I should walk because all of the evidence points in that direction.

- I have to take a walk or else I’ll go crazy.

- It seems like a good idea.

- I read somewhere that I should take a physical pause when I’m in a funk or paralyzed.

- There needs to be a balance in life.

- You can’t work all of the time.

- Everybody needs a break sometimes.

- Well, I did a lot of thinking about it, but I was getting stuck, and it seemed like I was going nowhere. So I decided that I really needed to do something and that I couldn’t just bog down in that state, so I came up with walking and it seemed to be the right thing to do for a number of reasons. So as you can see, it’s quite complicated.

Technically, the first two categories are reasons for your action. Your reason is your conscious purpose — the actual intention you are holding in mind to guide your action.

Everything in the last category actually adds up to “I don’t know my exact purpose, but it’s got something to do with fill in the blank with the words that came out.”

As you can see, the same behavior could be motivated by many different reasons.

Why you need to be clear on your reason for acting

You need to know your reason for acting. Putting your intention into words is how you get clear on the actual source of motivation for your action.

This is a general principle. Everyone has many vague thoughts and feelings. You make them clearer by putting them into words. If they are still kinda vague, that is okay (and normal). It is by starting with the vague words that you can then use logic to make them clearer.

When you ask the “why” question, what matters most is that you be honest with yourself. What is your real intention here? Do you know? There is no shame in answering the “why” question with an “I don’t know” or even an apparent rationalization. You ask yourself “why” for the purpose of self-awareness, not self-criticism.

When you get an “I don’t know,” you need to be curious and direct like a cat. What’s more interesting than your own motivation? Don’t you want to know?

It is true that many of the intentions I listed above aren’t “good enough,” in that you’d be wise to pause briefly to clarify them or challenge them before acting. But you need to know the actual intention that is operative in your mind. Knowing your actual intention is the only possible starting place for managing your motivation so that you can take constructive action.

Elsewhere (in a recent series of articles on happiness, particularly the article on productiveness), I have made the case that constructive action means action oriented to gaining values, not removing threats. In an earlier article, I fleshed out what it looks like to maintain such a value orientation and why it’s important for achieving your goals.

But as I explain in those articles, it doesn’t matter if your initial reason is threat-oriented or confused. Because however you understand it, your reason is connected to your values. So with a few more steps of analysis, you can get clear on the actual value you are after.

This is why you need to put your reason into words — so that you can see if you need to get clearer. When you “go by reason” you want to know the reasons for your action so you can vet the reasons for your action — delaying if necessary to sort out what action is in your rational self-interest.

Getting clearer on the value you’re after

Sorting out the value that underlies an intention is not that hard. For example, if you are avoiding a threat, you can just ask yourself, “What is the value threatened?” Say you are thinking, “I don’t want to be paralyzed.” Apparently you want momentum or action. Or if you’re thinking, “I don’t want to be sitting anymore,” you want movement or maybe flexibility if you’re feeling stiff.

If the words that go through your mind are, “I don’t know,” then you need greater self-understanding — a big value and a key element of acting rationally. You can easily gain more self-understanding by taking the action you already desire (walking) with the proviso that you will engage in self-awareness. Watching yourself and your emotional reactions will help you figure out what exactly you really like about walking and why it appeals to you. That would be a perfectly rational step to take if you are confused.

If a torrent of words comes out, you can record them and ask yourself, “Which part of this is really where my values are strongest?” Above, I gave this example:

Well, I did a lot of thinking about it, but I was getting stuck, and it seemed like I was going nowhere. So I decided that I really needed to do something and that I couldn’t just bog down in that state, so I came up with walking and it seemed to be the right thing to do for a number of reasons. So as you can see, it’s quite complicated.

When you reread this statement, it seems like the emotional energy is around “doing something … [to not] bog down.” This is a desire for momentum or progress.

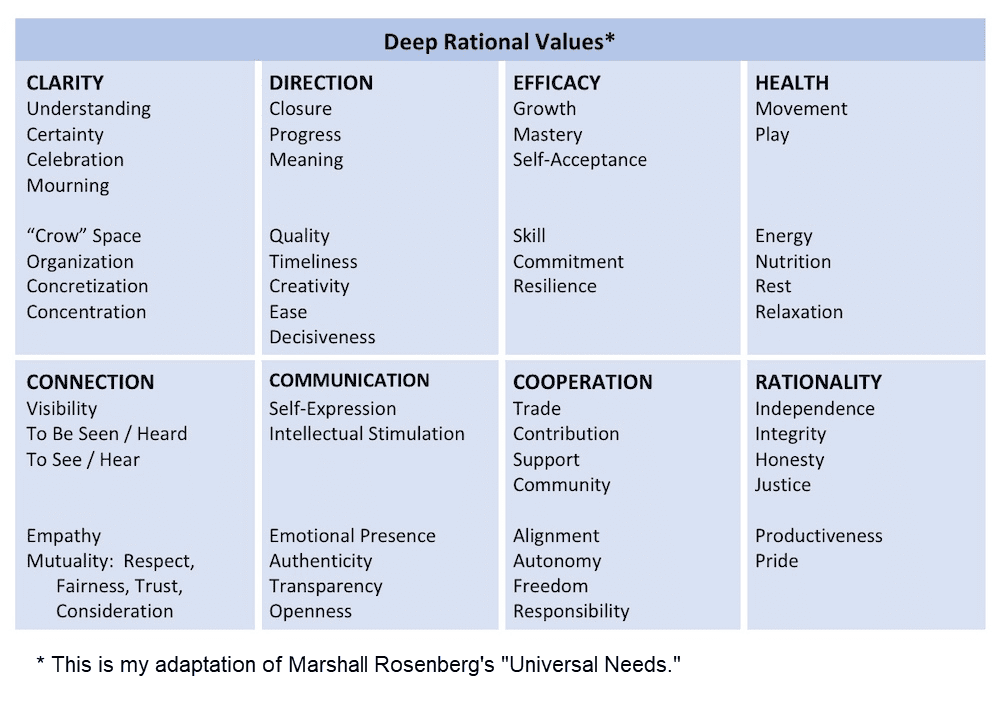

In another article, I discussed how you can change a purely logical “should” statement into one that names the actual value that motivates you. In that article I introduce a list of “deep rational values” that you can use as a cheatsheet to identify the values that are actually motivating you.

A big part of going by reason is translating muddled reasons into clear values. This is a learnable skill.

So one reason that words matter is that the words give you evidence of whether you really do know your motivation or not. And if you don’t, the words are your starting place for figuring it out.

Why words matter for the long run

But the words you use to state your reason for acting matter even more for the long run. It is the words that you use that program values into your subconscious databanks. When you put your reason into words, you also gain power to program your motivation for the future.

The actual cause of your motivation is your stored values. You have thousands of values, all of which have the potential to motivate you. They exist in a value hierarchy, in that some are stronger than others, and some are the means of achieving others. I explain how values form in another article.

But for the purposes of this discussion, what matters is that your present action will have an impact on your value hierarchy. Specifically, the value that you think you are acting to gain and keep will be strengthened. A value that you are aware that you could pursue right now but are not acting to gain and keep will be weakened.

The way that you formulate your intention makes all of the difference in what gets strengthened versus what gets weakend.

For example, if the Thinking Lab member I mentioned went for a walk to “feel good,” he would have been strengthening “feeling good” as a value to him, rather than some more specific value such as “fresh air” or “exercise” or “momentum.”

The problem with strengthening “feeling good” is that it is hopelessly vague and rationalizable. Why do people eat cookies when they’re on a diet? Because they want to feel good. Why do people avoid dealing with interpersonal conflicts? Because they want to feel good.

Unless you are a masochist, everything you do is to feel good. Acting “to feel good” is the error of emotionalism. You are treating how you feel as the test of whether an action is good or bad for you. But feelings are not reliable guides to that. You need to figure out whether the action that you think will “feel good” serves your life or not.

Moreover, if you are doing what “feels good,” you are consciously not going by reason. You are literally weakening the value of reason in your soul. If you are intellectually convinced you should go by reason, every time you don’t, you are undercutting that conclusion and making it harder to follow through on it the next time.

To reiterate, what matters for your motivation is not the action you take, but the meaning you give to it — the reason you give for taking it.

In other words, even if an outside observer would conclude that your action is serving your life at the moment, it won’t serve it in the long run if your reason for doing it is “to feel good” (an effect) rather than to gain a value (whose gain will indeed make you feel positive emotions).

If you conceptualize your reason for doing it as “to feel good,” this action is actually going to sow chaos into your values and make it more difficult to figure out what is in your rational self-interest next time.

This is such a waste. With a little effort, you can get clear on the values you expect to gain that you think will make you feel good. Focusing on them will strengthen them, organize your value hierarchy, and reinforce your commitment to reason.

Values as objective

Incidentally, the fact that the same behavior could be good for you if it’s based on your rational conclusion, and bad for you if it’s based on a desire to feel good, reflects a deep philosophical fact about values. They are “objective,” meaning they depend on facts that are out there in the world, on your context of knowledge, and on your intentional effort to figure out what the “good” is in this situation.

If you are an individualist, as I am, you recognize that there is no one-size-fits-all value hierarchy. Your values are highly individualized. Some broad principles can be formed about what is good for human beings in general. These principles are the virtues, such as honesty and integrity and productiveness.

But what is rational for you to do depends on what you understand.

There are such things as mistaken or distorted values. For example, sometimes people treat other people’s approval as a value. But you can make a general case that this is a mistake, because it subordinates your judgment to theirs. This handicaps you in identifying what is in your rational self-interest. The virtue of independence is the principle that helps you sort out this error. The principle of independence helps you then identify the actual rational value involved, probably a social value such as connection, cooperation, or communication.

But if you don’t understand the principle, you might buy into the idea that you should seek approval of certain authority figures (parents, bosses, etc.). Sooner or later this policy will put you into direct conflict with some other deep value such as honesty. When that happens, it will take some work to figure out what’s right. That’s when you’ll grasp the value of independence.

Once you see the logical value of independence, how do you weaken the pull you feel to get other people’s approval? And how do you strengthen the pull to be independent? You accomplish both of these shifts by a 3-part process. First, you make your continuing desire for approval explicit rather than suppress it. Second, you clarify for yourself what independence means in the present circumstances so you can see how it will benefit you now. This creates a small desire to take that independent action. Finally, you consciously act against the pull of approval, toward the pull of independence. That is how you reprogram your value hierarchy to align your subconscious values with your conscious convictions.

Pragmatism isn’t practical

The basic assumption of this article — that you can and should go by reason all of the time — flies in the face of common wisdom. The philosophy of pragmatism, which is rampant today, holds that reasons don’t matter. All that matters is the action you take — the behavior. Since your reasons don’t matter, it’s fine to manipulate yourself into taking what you “know” to be the right action.

This is all wrong. A pragmatic approach guarantees that you exacerbate the conflicts and contradictions in your value hierarchy. It directly contributes to the cynicism and skepticism of our age. With every pragmatic action, you become less able to identify your values. You increase the temptation to do the easy thing that is not good for you. You increase your resistance to taking the more challenging action that is in fact in your long-range interest.

The rational way to “do the right thing” is to know your reason for your action, specifically the deep values you are seeking to gain by that action. By being more aware of those values, you create a desire to take the action now. When you take the time to activate the value context, every action you take strengthens your rational values and contributes to both your short-term and long-term happiness. Now, that’s practical.

Brilliant. I’m currently listening to Lesson 9 – Reason, Emotions, and Certainty – from LP’s Advanced Seminars on Objectivism. Your article pieces these three things together so perfectly. Thank you, Jean!

Thank you, June. Yes, if you read OPAR carefully, you will see how much of my work is a direct application of the wisdom contained therein.